Actions against whitefly

How do I monitor for whitefly in my crop?

What are the key elements in an IPM programme for whitefly?

Given the cool and dull conditions that have been a feature of this year’s weather I’m not surprised we haven’t yet heard much about whiteflies in protected crops. As we move into July and hopefully temperatures start to pick up – and especially with poinsettia production getting into full swing – that could quickly change. Infestations can build up rapidly from small populations during warm weather, but they’re hard to spot when numbers are low and causing few symptoms.

Glasshouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) is the native species and the most familiar on protected ornamental crops. Cabbage whitefly (Aleyrodes proletella) sometimes migrates in from brassica crops on neighbouring farmland. It can be a problem on some ornamentals, including poinsettia, especially as controlling it with natural enemies can be more of a challenge than for glasshouse whitefly.

Growers of poinsettia, and other crops produced from imported cuttings, need to be especially vigilant for tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci), an alien pest still under official control in the UK. Any findings must be notified to the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) via your local inspector, who will then work with you to agree a control programme – the aim being to prevent the pest establishing in protected edible crops such as tomato where infection from the viruses it can carry would be devastating.

Some growers, including of poinsettia, have also had issues with honeysuckle whitefly (Aleyrodes lonicerae) in the last few years. Correct identification is important as it’s easy to confuse with B. tabaci – and you don’t want a statutory control needlessly imposed on your crop.

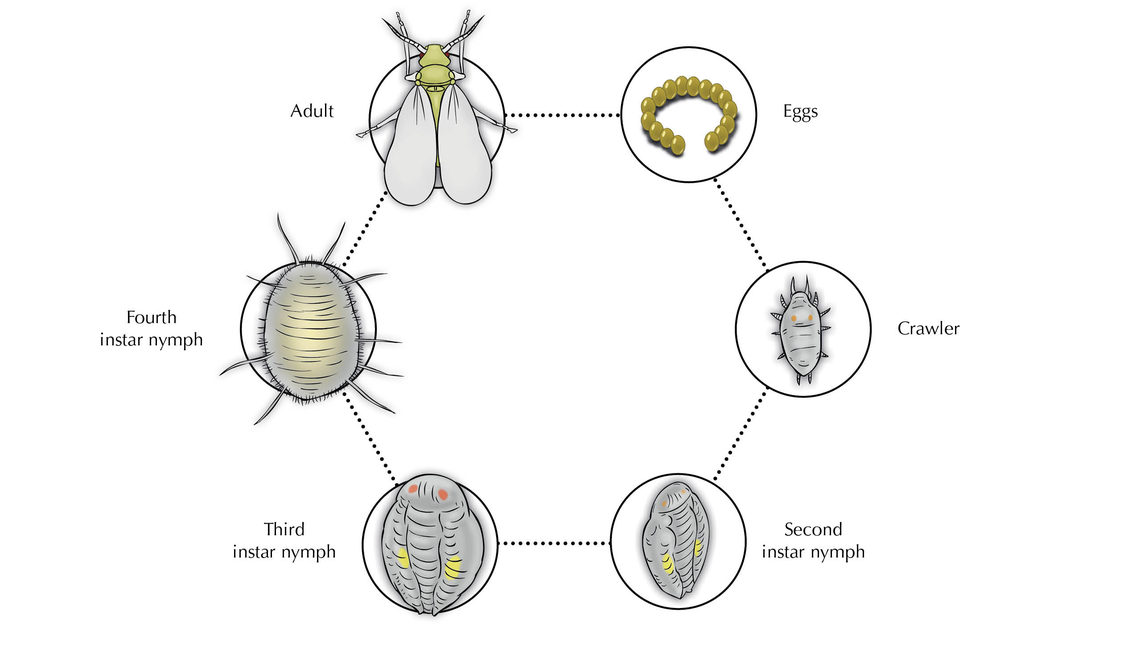

Glasshouse whitefly develops at temperatures between 8 and 30°C but the optimum is between 20 to 25°C, when populations can quickly get out of hand. At that temperature range it takes adults around 22 days to develop from eggs, though this varies a little with crop species. Preferred humidity is about 75-80% RH.

B. tabaci has a slightly higher optimum temperature range, at 25 to 28°C, and is very slow to develop below 16°C.

What to look for

It’s not always easy to distinguish between the various species so if in doubt consult an expert agronomist or your local plant health inspector. Control options will depend on which species is present.

Eggs and pupae of each species differ in size and colour – the pupae of glasshouse whitefly are straight sided, for example, while those of B. tabaci are rounded. Adult glasshouse whiteflies are larger than B. tabaci and fold their wings in a different way, over their bodies (see pictures).

Low numbers at the start of an infestation may result in little crop damage. Eggs are normally laid on the youngest leaves, near shoot tips, which is where you’re most likely to find adults too. As numbers increase you’ll start to see leaf yellowing, sticky honeydew and sooty mould, and plants will begin to lose vigour and quality.

Monitoring

Check imported cuttings and any other bought-in stock extremely carefully, especially for eggs and scales (the pest’s larval stage). When crop walking pay particular attention to potential ‘hotspots’ such as areas near heating pipes where infestations are most likely to take off first.

Set up yellow sticky traps, at a density of at least 100 cards per ha, in advance of a new crop if possible. The traps should be orientated to face south. Roller traps can help reduce whitefly moving between plant batches.

B. tabaci tends to be less mobile than other species so traps are no substitute for regular crop inspections.

Some growers use trap plants, such as aubergines, which attract the pest from the crop as a further aid to monitoring. These can also serve as banker plants for introducing and supporting natural enemies. You need to be careful, though, as the pest can develop quite quickly on these plants which can then become a source of infestation themselves.

Integrated management: biological control

As with any pest, starting clean means you’re already one step ahead. That includes controlling weeds in and around the greenhouse and making sure clean-ups between crops are thorough.

If your crop is being grown from bought-in cuttings or young plants, the success of your biocontrol programme will depend on knowing what treatments were applied during propagation. Just like their customers, Syngenta Flowers and most other international propagators implement integrated pest management measures as much as possible, which means you should be able to introduce your own biological controls as soon as your plant material arrives. It’s vital to check with them, however, as some chemical products can persist for up to 12 weeks and hamper establishment of parasites or predators; beneficial nematodes can be inhibited by certain fungicides, too.

Encarsia formosa, a parasitic wasp, is the most effective measure against T. vaporariorum, laying eggs inside whitefly scales. If B. tabaci is identified as the problem, Eretmocerus eremicus, also a parasitic wasp, is likely to be pivotal to the eradication programme you agree with APHA.

Predatory mites will target whitefly eggs, and are also central to thrips control. Transeius montdorensis (previously known as Amblyseius montdorensis) will hunt for eggs and first-instar larvae; Amblyseius swirskii works well at slightly higher temperatures and mainly feeds on eggs.

Bioinsecticides based on insect-killing fungi such as Beauveria bassiana or Lecanicillium muscarium can be applied on poinsettia and other whitefly-susceptible ornamental crops early in production as they tend to be unaffected by any products that may have been used in propagation, and they’re active against most larval stages and adults. They do need to be applied accurately (check out our ‘Art of application’ pages for tips) and when optimum greenhouse conditions can be maintained for the products’ constituent fungi to establish: temperatures between 18 to 30°C; humidity of over 60% RH for B. bassiana or 70% RH for L. muscarium.

A programme for poinsettia might start with a biopesticide application, followed by an introduction of predatory mites after plants have been pinched; and Encarsia or Eretmocerus released over the course of at least five or six weeks until they establish in the crop.

Chemistry

The products still available have a reasonable range of modes of action against whitefly but in all cases the number of applications you can make in a season is restricted for resistance management. They are best kept in reserve in case sudden changes in growing conditions, for example, mean whitefly populations start to outpace the biological controls.

Available active substances with on-label authorisations for ornamental plant production under protection include acetamiprid, buprofezin and sulfoxaflor.

Those available under an extension of use authorisation (EAMU) include fatty acids, flonicamid, pyrethrins with rapeseed oil, and spirotetramat.

Some are contact-acting, some are translaminar or systemic while some can only be used under permanent protection so check labels and EAMU authorisations carefully to pin-down which is suitable for your situation. Don’t forget you should always run a small-scale trial to check for phytotoxic effects with any combination of product or crop species or variety that’s new to you.